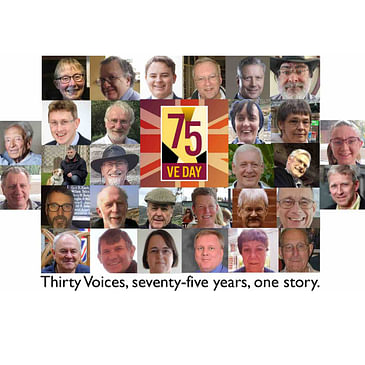

Originally timed to coincide with the 75th anniversary of VE day, this unique episode sees host Cathy Booth, joined by a whole cast of ringers, bust the myths about ringing during World War II. This is the full version of ‘thirty voices, seventy-five years, one story’. And what a story!

Bell towers across the country are currently silent due to the coronavirus pandemic. Unprecedented is currently a much-used word, but in this case not warranted, as we discover that 2020 is not the first time in living memory that ringing has had to stop.

Cathy discovers the true story of this earlier ban on ringing, brought to life from archived letters and articles, and the amazing true-life experiences of people who were there, including Dennis Brock, Britain’s oldest bell ringer and Eric Hitchins who rang his first peal on VE Day 1945.

The parallels with the current situation are striking. We discover that ringers’ concerns echo down the years, with their distress at the prospect of not being able to ring at Easter felt as keenly then as now. And, it appears, they were just as resourceful when locked out of their towers. Oh, and not much has changed with the locals either – always complaining about the noise of the bells, until, of course, there’s a ban!

We obviously all know end of the story as we wouldn’t all be here today had the ringers not got back to their towers, rolled out their recruitment plans and shared their passion for ringing. This is a hopeful, positive and inspiring tale – truly a story for our times.

Story behind the story

Knowing bell ringers were missing their ringing due to the Coronavirus ban, Cathy wanted to produce an episode of Fun with Bells that looked back at the time when bell ringers endured a similar ban – in World War II. Believing, as many historians do, that the ban was only lifted on VE Day, she asked Alan Regin to help her find bell ringers who had lived through the ban and could tell her about not being able to ring and what it was like being able to ring again.

Alan replied to Cathy, by return email, with suggestions of who Cathy could talk to and also sent 41 attachments, mostly scans of articles and letters published in the Ringing World during the war.

Cathy enjoyed reading the eloquent language in the Ringing World and realised that, as well as the original idea of interviewing those that were there, there was a story portrayed in these Ringing World passages that was not widely known. She then pondered how to put this across in the podcast until she hit on the idea of having current day bell ringers reading the passages.

As she only thought of the idea on the 23rd April and wanted the podcast to be published on 7th May, to coincide with VE day, there was only 2 weeks to get everything done.

Some of the people doing the recordings had links to their predecessors including Stephen Hoare from Thame who read the letter from Harry Badger.

And there were laughs as somebody sent in the wrong recording which contained frustrated expletives!!

Fortunately bell ringers are great at teamwork and with many people’s input, most notably Rose Nightingale and Steve Johnson the project was completed in time.

Top 5 take aways

- Why not take a leaf out of the book of the WW2 ringers and have a go at handbells during the lockdown.

- Now, like then, is the perfect time to put together your recruitment plan for when ringing returns.

- Why not research the local history of your tower and the local paper reports of the time. Do you know anyone who remembers the bells being rung to celebrate VE day in 1945?

- Find out more about the ringers who lost their lives in the Second World War in the The Central Council Rolls of Honour https://cccbr.org.uk/resources/roh/

- Many ringers had been planning to ‘ring for peace’ to commemorate the 75th anniversary of VE day. Although that’s not possible, why not think about marking the day in some other way https://ve-vjday75.gov.uk/

Comments on this episode from our legacy website:

bethemmajohnson: (2020): Thanks for this podcast Cathy, really interesting and entertaining.

The abridged version of this episode is called 'Lifting the WWII ban on ringing'

Sponsor: This podcast is sponsored by the Association of Ringing Teachers (ART). To find out more about learning to ring, learning to teach or other resources to support your ringing go to bellringing.org.

Steve Johnson: [00:00:04] The current government advice based on science is to stay at home, protect the NHS and save lives. Like other activities, bell ringing is fundamentally affected by this in a way not seen since World War Two, when the government of the day singled out a special purpose for the bells. Many people believe that the bells only rang again on VE Day, but in this episode, 27 Bell Ringers of today tell us a much more interesting story as they read the elegant words from the contemporary records in the Bell Ringers paper The Ringing World. At the end of our story two bell ringers, tell us about where they were on VE Day in 1945.

Cathy Booth: [00:00:47] In Britain, we had church bell ringing for centuries until suddenly on the 13th of June 1940, nine months after the start of World War Two. People heard on their wireless that church and chapel bells were not to be rung, except for if there was an invasion. But who were the persons that decided that the bells should be used in this way? We find this out in the House of Lords in 1943, Lord Geddes is quoted in Hansard as saying.

Simon Davies: [00:01:21] "My Lords, you may be interested to hear the origin of the order about the ringing of the bells." It was at Tunbridge Wells, Lord Ironside, who was then chief of the Imperial General Staff, was in my room and there were also present General Thorn and I think I am right in saying my noble friend Lord Norris. We had just got the first detachments the local defence volunteers formed and the only part of the local defence volunteers who had arms at that time were the Kentish and some of the Sussex companies. The whole thing was very nebulous, and it was thought that at any moment we might see parachutists dropping down from heaven. I think it was the chief of the Imperial General Staff who said, "How are you going to get these local defence volunteers together?" if parachutes suddenly appear and somebody in the room. Not I, but I could not be sure which of the others said "Why we will ring the church bells until we can think of something better." That was in early May 1940, and the War office had been thinking of something better ever since. That signal at that time was supposed to be used only in the counties of Kent and Sussex and in the rural areas. But somehow or other, the order became more or less sacrosanct and spread all over the country. It was trimmed and pruned and sprouted new legs and arms, and it became one of the essential pillars of the defence of the country. It is a complete mystery to me why that it should be home, but I am assured by war office representatives that it is.

Cathy Booth: [00:02:58] But now let's progress chronologically, starting back in 1941 with a poem not published until much later. It's by the poet Mr AP Herbert, and it's called Bring Back the Bells.

Jill Belcher: [00:03:13] If we cannot inform the town, that parachutes are coming down, without inviting Huns to search for targets in the parish church, the old inventive British brain had better surely think again.

Cathy Booth: [00:03:33] In June 1942, the Ringing World reflected that

Bob Christopher: [00:03:37] On June 14th 1940, an order in council was made prohibiting the ringing or chiming of church bells, except by the military or the police as a notification of the landing of enemy troops by air and during the two full years since then, the bells of our churches throughout the land have been silent. No such thing had ever happened before. For more than a thousand years, almost from the time when England became a Christian country. The church bells had been one of the most familiar and intimate features in the ordinary life of the common people. They called the faithful to prayer. They knowled the departing souls, they made merry at weddings, they announced victory, they welcomed the great men of the land. In one way or another, they voiced the aspirations and ministered to the needs of the community so that they became almost the most precious of all the parish possessions. It was not for nothing that England got the name of The Ringing Isle. No doubt in modern times, with the vastly increased interests and changing outlook, the old sentiment has been largely obscured and to some extent lost. Yet it still survives below the surface for it is in the blood of Englishmen. How otherwise can we account for the large sums of money that was spent annually to restore old bells and supply new ones? And to very many people, the silence of the church bells means a real loss. We as Ringers have a special deprivation for we are debarred from that activity we most delight in and by which, so we are assured by competent authority, we can best serve our church. But we accept the situation, not willingly and still less gladly, but without complaining. If this is one of the sacrifices we are called on to make for the sake of England, we are ready to make it and to count it a small thing. We do not question the right or the competence of the persons who decided the bells should be used as a warning, though we may doubt whether they would actually be very effective for that purpose.

Cathy Booth: [00:05:55] In January 1942, this letter was typical of the content of the Ringing World.

Graham Nabb: [00:06:02] Dear Sir, Is it not time to stop worrying about needless trifles? Some have worried over the Central Council and its officials and others over the ban. No one likes it, least of all us who have rung on Sunday since boyhood. But my personal opinion has always been that once the bar was put on, it would not be lifted so long as the Germans hold the coastline of the continent. There will be plenty of time to lift the ban when the danger of invasion is passed. I believe he will attempt it by air just to satisfy his own people. If we're honest, we must admit that even if we were allowed to ring now, not half the towers could do so. There are no Ringers available. Writers are also worrying why the Central Council does not meet, if they did would that help the war effort? So far as I can see, no. Our president and secretary at present, we do know are helping the thing that really matters, the war and other members are doing their share. We do know that our exercise is safe when we have won, but if we lose, it will be gone. Let no one think the hun would stand peals being rung. For one thing, we should not have the bells. He would put all that metal to other purposes. In conclusion, do not be so downhearted about after the war ringing. It may not be so posh, but it will recover in time and it will be a real treat to everyone if we can only ring good rounds. -A.H. Pulling the Grammar School, Guildford.

Cathy Booth: [00:07:51] However, Bell Ringers were finding inventive ways to practice during the ban. As explained by the evening news.

Nick Brett: [00:07:59] Bells or no bells, the Ancient Society of College Youths famous old fraternity of the bell ringing craft in London, has been meeting every fortnight at Mears and Steinbanks in White Chapel Road to keep up their change ringing practice with handbells. In the past fortnight also, there has been practice ringing on the bells of St Botolph's Bishopsgate, with the clapper's fixed and the bells thus silent. It has not been decided at the moment I understand what change ringing there will be in the city and immediately outside. St Paul's Cathedral has its retained band of Ringers. It's bells were being examined today. St Botolph's bells can be rung, but those of St Sepulchre’s, Holbourn are probably not in fit state for ringing. The city of course, has lost many historic peals through enemy action. The 12 bell peels of St Bride's Fleet Street, St Giles Cripplegate and St Mary Le Bow Cheapside, the 10 peal of St Clement's Danes and half a dozen or more 8 bell peals have gone since the ringing ban was imposed in June 1940. One of the problems of arranging a changing ringing programme is manpower. In the ancient society, which keeps up the old craft in and around the city, were many young enthusiasts who have gone into the services now. Their places cannot be taken by practised helpers.

Cathy Booth: [00:09:18] Whilst others were thinking ahead to after the war,

Phil Tremain: [00:09:23] Dear Sir. Most writers recently on the subject of post-war reconstruction of dwelt, mainly on the difficulties facing the exercise, whilst I fully appreciate that there are difficulties, I feel that there is very definitely another side to the picture. Is it not a fact that when the ban is lifted, the great majority of the general public will welcome the sound of the bells? This strikes me as an opportunity for Ringers to get busy and make an appeal for recruits who will be needed to fill the inevitable gaps. How is this to be done? Certainly not by sitting down and bemoaning our difficulties. Ringing must be made attractive if people's interests can be sufficiently roused, I think it is only reasonable to assume that recruits will be forthcoming. Generally speaking, I do not suppose that one person in a thousand, has the faintest idea of what ringing is, and I feel that it is this ignorance, which is the main obstacle to be overcome. So we must devise ways and means to stimulate people's interest and attract them. If I may make a few suggestions, I can think of a few ways of tackling the problem. Subject of course to varying local conditions which will always need considering: get hold of the person, ask him to call a parish meeting. Then the Ringers can put the case over. A demonstration of handbell ringing will help if it can be arranged. Another idea? Why keep the belfry door closed at all times? Why not extend an invitation to anyone interested to come and see for themselves how it is done? Say on Sunday mornings? By all means of course, the door must be locked when peal attempts are being made, but on other ocasions I see no necessity for it. People will obviously not come unless they are asked, and the invitation must come from the Ringers themselves. In a nutshell, we have got to do a little propaganda work. An unpleasant word but it covers the case, as I see it better than any other. The time will be right after the war and we must not miss the opportunity which will be presented. It is a call to action. -R.W. Daniels, Captain RASC.

Cathy Booth: [00:12:13] But then in November 1942, Bell Ringers had an opportunity to ring again given to them by Churchill himself after victory in the Battle of Al Alamein.

Natalie Brett: [00:12:28] The Prime Minister's great speech in the House of Commons altered everything. He explained in detail what had happened and at the climax of his speech, he used these words. "Taken by itself, the Battle of Egypt must be regarded as an historical victory in order to celebrate it, directions are being given to ring the bells throughout the land next Sunday morning, and I should think many who will listen to their peals will have thankful hearts. Then the country knew on the highest authority that the victory was not merely a brilliant success, but the smashing victory for which we had so long been waiting and longing. Small wonder that the country took the raising of the ban as a symbol of a greatness and completeness of the triumph. Or that a great newspaper like the News Chronicle should label it's comments on Mr Churchill's speech. The bells will ring. During the following days, the press comments on the matter were many. Like the usual references in newspapers, to bells and ringing, they were seldom well-informed, but that signifies little. The great thing is the evidence of the stronghold church bells have on the affection and sentiment of the people of England. For us Ringers, it is a most encouraging sign."

Jenny Lawrence: [00:13:56] The way the general public and the national press received the news that the ban on ringing was to be lifted last Sunday, was wonderful, heartening and almost unbelievable. At a time more crowded with world shaking events than any period since the fall of France two and a half years ago, church bells were given a foremost place in the news and everywhere people were looking forward to hearing once again the music of the parish steeples.

Cathy Booth: [00:14:29] The pressure was on and the then president of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, Mr E.H. Lewis, gave a statement that was to be printed in the national press.

Simon Linford: [00:14:41] May I, through you, ask the public to be indulgent in their criticisms of any ringing which may be on Sunday morning? Ringing is an art which requires much practice, and for nearly two and a half years there has been none except in a few towers upon silent bells. Many bands will be short handed as their members are in the forces. Those who are left will do their best, but the quality of the ringing cannot be as good as we could wish.

Andrew Wilby: [00:15:09] On the following day, the Evening Standard proclaimed in heavy headline that St. Paul's bells cannot be swung but it contradicted the assertion in the text. Mr A.A. Hughes, who is both a member of the Society of College Youths and of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which has been making London bells since the 16th century, is confident the bells of both St Paul's and Westminster will ring out a full chime of peacetime strength. He said "When we held the 305th anniversary luncheon of the society last week, 104 of our members were present so that we can still ring quite a number of bells. This business of ringing the bells is not quite as simple as the government's instruction make it appear to be. Our telephone is going every 10 minutes, and the calls are all coming from churches which want their bells put in order at short notice. It just cannot be done. There you are another message from the country has just been put in front of me. They want 10 clappers installed tomorrow!"

Cathy Booth: [00:16:14] So what was ringing like after three years of silence? This letter in the Ringing World explains,

Stephen Hoare: [00:16:21] Dear Sir, it is surprising how after an enforced silence in ringing, members come together on an occasion like November the 5th. Here in Thame many members of the young band that existed before the war are serving with the armed forces. After the welcome news that the ban had been lifted for the Sunday morning, we could only muster four Ringers at the outside. At least we thought so! But by Saturday evening nine men had promised to come and that number arrived punctually at 10 o'clock on Sunday morning for an hours ringing. At least two of these Ringers had not handled a bell for upwards of 20 years, and although there was a certain amount of rustiness, the ringing on the whole was good.

Cathy Booth: [00:17:12] So now the Ringing World led the campaign to lift the ban.

Chris Wright: [00:17:16] One result of the ringing for victory has been a renewal of the hope that the ban on church bells will be lifted. It has all along been abundantly evident that very many people have regretted that it ever was imposed. To the regular churchgoer the absence of the familiar sound gives an impression that something important is wanting in the service and even among the general public, there is a strong feeling that there is something lacking in an English Sunday when the bells are silent. This was well expressed in the leading article of the Eastern Daily Press we reproduced last week. Whether these hopes will be realized we cannot say. The exercise would gladly welcome any raising or modification of the ban, but it is only right to recognise that there are some important objections to it now it has been on so long. It was a mistake in the first place to reserve the bells for the purposes of warning. We do not question the right of the government to do so. We do not think that there is anything in the argument that the bells ought not to be used for the purpose because they are church bells. We do not think it has in the slightest degree led to the bombing of our churches. But we are quite sure that as warnings, the bells would be completely ineffectual and useless, even if efficient means were found of sounding them immediately they were needed. The range of their sound is very limited and would reach only a tiny fraction of the country. Last Sunday week, when the whole country was listening, there were millions who never heard them. We must not blame the persons responsible overmuch. The ban was imposed at a time of the direst national peril. How dire we did not know at the time, the authorities had to make provision against all sorts of evil chances and to make use of any means that lay to their hand? It is no great wonder that someone suggested as a warning, the bells of the churches, the ancient alarm signals.

Cathy Booth: [00:19:51] And it was reported on elsewhere in the press:

Andrew Johnson: [00:19:55] Last week, the Church Times wrote "The country as a whole, and churchmen in particular are grateful to the Prime Minister for bidding the church bells break their enforced silence on Sunday. The time has surely come for some modification in the ban on church bells. If no other invasion warning can be supplied, it should be possible to devise an easily recognizable alarm signal to be rung on the bells, which would be distinguishable beyond possibility of error from the regular call to worship. In some places, the break with habit may have done no harm. In others, the loss of the customs' summons has had a definitely bad effect on church going." In the Guardian. The Rev. M.H Lewthwaite wrote. "Why not ring the church bells every Sunday, at least? Why keep the bells silent? I have never understood it. It is surely bad policy in every way. If it is necessary to give warning of the invasion by bells that can be done, we do not ring a toxin for divine service or at midnight. If a warning by bells is requisite, it can be given. But why stop our bells? Cannot the military or other authorities be instructed about this? The people of Britain desire to keep their bells." In the spectator, Janus, who writes the weekly notebook said "Having felt some slight questioning about the wisdom of last Sunday's bell ringing as a savouring of exuberance. I admit that the authorities were completely right. The sound of the peals from different villages banished all doubts on the spot."

Cathy Booth: [00:21:40] Bell Ringers were not always completely happy with how the national press reflected their art.

Judith Frye: [00:21:46] Dear Sir, A few days ago, when I opened a copy of The Daily Mirror, I was amazed to see a photograph of two young girls swinging in distinctly ungraceful attitudes upon bell ropes several feet from the floor. Upon reading the note, which accompanied the picture, I was still more amazed to be informed that this was a learner's class in progress in a Buckinghamshire tower and that the incident illustrated formed part of the syllabus. When I first learned to handle a bell some 14 years ago, one of the things which was impressed firmly upon my mind was the fact that one should never lift one's feet from the floor while ringing, and I feel sure that the opinion of competent Ringers will be that I have been correct in pointing out this fact to the not inconsiderable number of pupils whom I have taught to handle a bell since that time. We really should be grateful to the Daily Mirror for its interest in our art and its repeated requests that the ban on ringing might be lifted. These facts make it the more to be regretted that the paper's representative should have been so misinformed as to be led to believe that the childish antics depicted, form part of the instruction required to produce a capable Ringer. -R.D Sinjin Smith C.F, Catterick Yorkshire.

Cathy Booth: [00:23:04] Not only was the issue of the lifting of the ban being debated in the press, but also:

Simon Head: [00:23:11] In the House of Commons on Tuesday last week, Mr A.P Herbert, independent Oxford University, asked the War Minister whether in the light of recent events, he would reconsider the decision to use church bells as a military signal and adopt some arrangement which would not deprive the community of the bells. In reply, Sir James Grigg said the question was now being considered. Later in the week, Mr Attlee informs Mr Driberg, Independent, that the question of permitting the bells to be rung on Christmas morning was being considered. Asked how soon consideration was likely to be, he replied, "I cannot say." Mr Stokes, Labor- "In view of the fact that in many parts of the country, the bells are not heard at all and that they are of no use as invasion signals. Why not use the sirens as invasion signals and allow the bells to be used normally?" It was greeted by cheers. The Dean of Winchester, preaching in his Cathedral, said "We can look forward to the time when the bells will ring again. I confess that I wish the government would think about some fresh method for giving notice of attempted invasion. It surely cannot be beyond the wit of man. And let us ring our church bells every Sunday, and I am sure the Bell Ringers of England would say the same. I believe it would be of great benefit to public morale and religion and remind us that we had entered on a new phase of our struggle. I wish the church authorities would concern themselves with making representations to this effect."

Cathy Booth: [00:24:59] Even at the last moment, there was no certainty that the ban on ringing would be lifted. The Ringing World editorial for the 25th of December 1942 reported that although the demands had not been met with a flat negative at the time of writing, they did not know whether ringing would be allowed at Christmas or not. However, the Ringing World's subsequent review of 1942 read.

Chris Bullied: [00:25:27] For Ringers the most outstanding event of the past year was the temporary lifting of the ban and the victory ringing for the Battle of Egypt, although there was very short notice given, Ringers everywhere mustered in full force in the belfries and on the whole, the ringing was reasonably good in quality. The interest taken by the press and the general public was surprising and was a good augury for the future. At one time, it seemed likely that the ban would be permanently lifted or modified, and much pressure was brought to bear on the authorities to that end. It did not succeed however, further than securing permission for ringing during a limited period on Christmas morning. We may not have heard the last of the matter. The victory ringing stirred up a great deal of enthusiasm, and apart from that interest has been generally well maintained among those to whom we shall have to look for leadership in the days of reconstruction. The two principal luncheons of the year, the Henry Johnson commemoration at Birmingham and the College Youth's annual feast were well attended and highly successful.

Cathy Booth: [00:26:36] The letters pages in subsequent issues of the Ringing World were buzzing.

Stuart Newton: [00:26:40] Dear Sir, every effort should be made so that the church bells can ring on Easter Day. It is one of the festivals when the bells have a special message for the people and this Easter, that message is even more valuable than ever. The victory bells last November would have lost their real meaning if the bells at Christmas had been silent. Lifted again on Easter Day, it will be a further strengthening of the faith of the British people. What greater ideal can the bells ring out for than the message at Easter? Victory over death. Let us bow our heads in silence for a minute on that day in memory of our dear ones who have gone down in this war. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them. Charles Turner, Captain, St Mary's Ringers Dover.

Alison Davies: [00:27:40] Dear Sir, may I add a small footnote to your very sound and statesman like leader in the Ringing World of February 19th. Before the war, people were continually bursting into the newspaper columns, passionately demanding in the name of their poor nerves that church bells should be silenced. Since the prohibition of ringing, the papers are full of equally passionate letters, angrily demanding that the bells should ring again. That is human nature. We never know how we value anything until it is taken away. Oddly enough, I do not remember to have seen any letter or paragraph saying, "well, thank Hitler, that horrible noise stopped". The Ringers can afford to smile and bide their time. Let them, meanwhile, carefully collect and preserve all the published evidence that people like bells, want bells and are indignant at the silencing of bells. Then, when the ban is lifted and all the drearys start to once more protest, that bell ringing is useless, burdensome, dangerous and ought to be abolished. There will be an answer ready for them. Dorothy Sayers, 24 Newlyn St, Witham, Essex.

Richard Booth: [00:28:50] Dear Sir, The ban on bell ringing is still in force. Why? I, for one, cannot say. In my opinion, bells should be allowed to be rung during daylight and it should be a punishable offence to ring after dark. With regard to Easter Sunday, if the ban for that day is lifted, we should be allowed to ring for evening service as well as matins, because some churches have five services in the forenoon. There have been several tests of the sirens, but no tests by the military or police at bell ringing. I cannot imagine for the life of me why on earth the authorities did not give instructions for the bells to be rung. G E Simmons, 57 Mornington Avenue, Ipswich.

Oliver Bouckley: [00:29:39] Dear sir, In reference to your leader in the Ringing World, Bells at Easter. If the ban is lifted and we are permitted to ring at Easter, I would welcome the suggestion of Mr Carew-Cox that ringing be allowed in the evening, as well as in the morning. There are no doubt many like myself on shift work who have to be on duty during some part of Sunday and in many cases could not take part in the ringing if only permitted in the morning. If ringing could be permitted to take place morning and evening, many Ringers could avail themselves of the opportunity of being present at their respective towers either morning or evening to fit in with their off duty periods. In reference to the time allowed for ringing. I would suggest that the authorities allow this from 10am till 1pm and from 5pm till 6.30pm. Arthur E. Shrimpton, St Stephen's Ringer's, Redditch, Worcestershire

Cathy Booth: [00:30:40] Three prominent Ringer's talked of the future.

Matthew Turner: [00:30:43] Mr Duffield spoke of the hard tasks ahead of the ringing societies. If change ringing was to be restored to the proficiency it had attained in the past two generations. He shared the views expressed by Mr C T Coles and Mr A P Peck that insofar as cooperation between the various societies could exist, that cooperation would be forthcoming. And he believed that all who had the welfare of the ringing exercise at heart would play their part in getting the bells ringing again as soon as the ban was lifted

Cathy Booth: [00:31:10] On 31st of March 1943. The Ringing World reported that the matter had been raised in the House of Lords

Steve Johnson: [00:31:19] Last week in the House of Lords. The Archbishop of York, Dr Garbutt, raised the question of church bells and moved that the ban be lifted or modified. He had the support of several influential speakers and no one spoke in favour of maintaining the banning order except Lord Croft, the joint under-secretary for war, who pronounced the official decision that the ban cannot be removed. There is however, a very considerable amount of feeling on the matter, and the last about it has not yet been heard. The Archbishop said that the edict about church bells came into force at a time of great stress and difficulty. Since then, many things have happened. But among the various changes and modifications, one ban remained unchanged. For nearly three years, 12,000 parishes, with three exceptions, had had their bells silenced in case they should come into one of those parishes, a certain number of Germans. Psychologically, the silence of the bells has had a very bad effect on the people. Under the regulations, the bells had to be rung if 20 paratroops drop in a parish. But in the towns, it is not easy to know ecclesiastical boundaries. When I went to South London, I found that the people rarely knew their parish church, so I had to ask for the nearest public house. If paratroops came, a policeman or other official would first have to be sure of the exact number of them and then get an ecclesiastical map to see in which parish they had fallen.

Steve Johnson: [00:32:58] There are some people who hate bells and regard their silence as the one and only alleviating compensation of the war. But most people deplore their silence. This drew cheers from the house. He was not suggesting that the danger of landings has passed away. It was possible that when a second front was opened up, every form of attack would be made upon this island. But he did urge that it was unnecessary to silence the bells, which for centuries had been so closely connected with both the religion and life of the country. Church bells could be rung in a different way to give warning, they could be clashed or clanged. If the noble Lord who was going to reply for the government tried to ring a bell at the nearest parish church, the noise would soon cause consternation to all those who heard it. This to laughter. The government could lift the ban entirely and replace it in a few hours notice by means of the wireless. It could lift the ban on the town churches and leave it on the country or leave it that the bells were not to be clashed or clanged, except as a warning. Lord Motestone said that to rely seriously on church bells for warning was not only a disadvantage, but a positive danger. If the ban were removed, it would add to military security instead of lessening it.

Steve Johnson: [00:34:23] Lord Quickswood said "that to multiply regulations which were not necessary was unwholesome from the point of view of public morale". Lord Geddes said that he was present at a meeting in May 1940, when the question was asked What can we use for a warning? And someone who he could not remember said "We will use the church bells until we can find something better." It was intended for purely local purposes throughout Kent and Sussex. The war office had been trying to think of something better ever since. He had asked one high officer after another what he thought of the regulation, but he hesitated in that house to quote most of the replies. He was sure no one knew what the regulation was supposed to do, and it was kept only because no one would take the responsibility of agreeing to lift it. Replying for the government, Lord Croft, joint undersecretary for war, said the whole question had been reviewed very often. Every alternative form of warning had been considered, including a variation on the use of sirens, but none had been found satisfactory. We are convinced, he said that, "the bells are the only signal which can be regarded as a distinct and definite warning". Asking leave to withdraw his motion, the archbishop said if the government does not make some satisfactory arrangement on this subject soon, I shall be bound to bring the matter up again.

Cathy Booth: [00:35:51] But he didn't have to because, as was reported in the Ringing World

Helen McGregor: [00:35:56] Last week in the House of Commons, the Prime Minister replied to Mr Green-Wood, member for Wakefield, and answered the ban on the ringing of church bells would be removed. Mr Churchill said "The war cabinet, after receiving the advice of the chiefs of staff, has reviewed the question in the light of changed circumstances. We've reached the conclusion that existing orders on the subject can now be relaxed and the church bells can now be run on Sundays and other special days in the ordinary way to summon worshippers to church. The new arrangement will be brought into effect in time for Easter". On the following day, the press was informed that the control of noise order, which had been amended to give effect to the Prime Minister's announcement, prohibits the use of church bells on days other than Sundays, Good Friday and Christmas Day, and provides that the bells may be rung only for the purpose of summoning worshipers to church. They must not be used for weddings or funerals. A further statement by the Ministry of Home Security explained that the government's object in restricting the occurrence on which bells may be used was to avoid misunderstanding from any ringing at times when the public do not expect it. Mr Churchill's original statement was received by the house with cheers and by the press with general approval. In a leader, the Times remarked "The opinion was widely held that the silencing of the bells could no longer be justified on strictly military grounds and that it should be possible to devise some other means of warning in the case of invasion. Future historians may well look upon the decision as a milestone in a long journey, but those who in 1943 are concerned with home defence, whether as regular soldiers, Home Guard or civilians will not be so foolish as to neglect continued preparedness against invasion on a substantial scale".

Helen McGregor: [00:37:54] Lord Croft, in his reply in the House of Lords recently, implied that the authorities still regarded the ringing of bells as the only distinct and definite warning of invasion. Now that view has been changed, some new form of warning presumably will be substituted. For the rest, no one must expect immediately to hear a joyful clamour arising in the old places. Bell ringing is a difficult business. Badly rung bells would be a mixed blessing. And in wartime, it'll not be easy to find those who are competent. With arms lifted to clutch the rattling ropes that race into the dark above and the mad romping ding. Some belfries have vanished altogether. In others, they will have to be a reconditioning of bells and ropes. But however few and simple the chimes, it will be good to hear again what Lamb called "the music bordering nearest heaven". The Daily Telegraph wrote "Gratitude to the Prime Minister and the war cabinet for reaching the conclusion that the church bells can now be rung on Sundays and other days to call people to worship. It's tempered with general wonder that the authorities have taken so long to make up their minds to restore the liberty of ringing. Like every other emergency measure, the prohibition was accepted with goodwill and has been patiently endured, but the public has never had any explanation how this particular form of warning would be effective". The Daily Mail said "For only the third time in 32 months, the church bells of Britain, mute with a stunning suddenness since France fell, are to ring next Sunday. Not as once, for long and heartrending months, we feared they might ring urgent clamour with alarm to announce the silver frontier of a sea, which has guarded us for a thousand years, had gone the way of all the frontiers of Europe. Not even as they ran with jubilation for the victory of El Alamein. Next Sunday and thereafter, the bells will ring as they have always rung. Their sound sweet with distance as it drifts across the sunlit meadows strong as it shatters in the city street. Marks not an isolated, there's a permanent victory. Britain has repelled the threat of invasion. Henceforth, the bells may fulfill their ancient function. Those golden throats that call the world to God".

Helen McGregor: [00:40:24] The Daily Express wrote "German air power silenced the British church bells in June 1940. For three years, except for the celebration of El Alamein, they have kept bells silent by the belief that Hitler could invade Britain. What makes it possible for the church bells to ring again for Easter 1943? British air power. It's smashed the German invasion in 1940, and this year with American air power, it's going to help in the smashing of German invasion power forever". Last Sunday, the Sunday Times began a striking leader with the following passage "Bells at Easter, we scarcely expected to hear them, except for some great victory. But there's a special appropriateness in the breaking of the silence of the steeples on Easter Day for Easter bells, are bells of victory. They are in part of that annual rejoicing of Christendom over a triumph more momentous and decisive, according to its faith than any other ever could be".

Cathy Booth: [00:41:29] The whole affair was summed up in the leader on the front page of the Ringing World on the 30th of April 1943,

Jill Belcher: [00:41:39] "The government's decision has been generally welcomed by the press, but we do not ourselves agree with the construction". Some papers put upon it. The Daily Express, the Daily Mail and to a more cautious degree, the Times, "See in it evidence that the government are now convinced that a full scale invasion of this country has passed the bounds of possibility. It is certainly true and has been for nearly two years that there is no immediate fear of invasion, and to conquer this country by the landing of armed forces is a very difficult matter, so difficult that during nine centuries it has never been attempted and only on two occasions has been seriously contemplated. The difficulty can be summed up in one word, the enemy must gain control of the seas, and control of the seas means not only being able to pass an army onto our shores, but to supply and reinforce it. The difficulties remain the same throughout the ages, but in one important respect conditions in this war have greatly altered to our disadvantage and have largely robbed us of the security we enjoyed for so long. Control of the sea, in such a restricted area as the English Channel, now depends as much, possibly even more upon mastery in the air, as on the supremacy of ships. Germany could not hope to rival us in war vessels. She could and did hope to overwhelm our air force. The attempt was made and it failed. How badly it failed was perhaps better realised in Berlin even than Whitehall. And when Hitler turned to bombing our towns and later through his armed might against Russia, he confessed that a full scale invasion of England was not then practicable, just as Napoleon did when he broke up his camp at Bolougne and turned upon Austria.

Jill Belcher: [00:43:57] This is not to say that another attempt at invasion cannot and will not be made. But first, they must be vast preparations which cannot be hidden. All this, of course, was known to our military authorities and is a poor complement to the intelligence to suggest that they have only just realised it. The ban has not been lifted because of any dramatic change in the character of war, but because it is known that bells would be useless as warnings. It is quite certain that this has been known for a long time, almost from the beginning for the military authorities have left them out of their calculations, have not included them in their tests, and have taken no adequate steps to find out whether they would be available or effective. The soldiers ignored the bells. The people at the war office sat tight, and no one was found able and willing to take the responsibility of reviewing the matter. But when the thing was brought into the light of day by the debate in the House of Lords, the Prime Minister took the matter into his own hands and did what some authority ought to have done long ago. He called the chiefs of staff together and asked them plainly whether they relied on church bells as an essential part of their defence plans. When they told him they did not, there was an end to the matter. The use of bells as a warning disappeared and nothing was put in its place. It was a small matter compared with the great issues of war. But it shows the value of having a strong and able man in supreme control.

Cathy Booth: [00:45:55] A feature article looked forward to the future of ringing.

Jonathan Stuart: [00:46:00] The ban has been lifted. Not completely, but sufficiently for our immediate needs. And before we consider how best to meet the problems which confront us, it may be well to take stock of the loss and gain we have sustained by these nearly three years of silence. At first sight, it may seem to have been all loss and no gain. Our bells have been dumb and our activities have been brought to a standstill. And whether we look upon our ringing as part of the service we can render to the church and nation, or as an absorbingly, fascinating recreation, we have had no small proportion of our interest suddenly and completely stopped. The deprivation has been all the more severe because there were good reasons for thinking it was not really necessary. But that is now largely passed and it is no good regretting the peals we might have rung or the tours we might have enjoyed, had things been normal. What we cannot escape is the permanent loss the exercise has suffered, and certainly there is loss. During these years, the normal wastage caused by death and increasing age and by loss of interest has not been abated, while the replacement by new recruits has been negligible. Today the exercise is far weaker than it has been for a very long time. Not only temporarily because so many Ringers are away serving the country, but permanently because there are no new members ready to take the places of the old ones. Much of this is, of course, due to the war and would have happened in any case.

Jonathan Stuart: [00:47:53] But the ban has accentuated the evil and made it exceedingly difficult to keep interest alive. Not only so, but once a practice has definitely lowered the standard of ringing and striking, and that at a time when it is more than ever essential that the bells should be rung well. Those are the facts we must face. It is no good pretending we have not had loss and that we can carry on as if there had been no long silence. Nor, though it is well to take a hopeful view of things, should we deceive ourselves by the satisfaction most of us feel at finding things are not so bad as we feared they would be, and as they well might have been. So much for the loss, have we any gain? Well, strange and paradoxical as it might appear, we believe that the gain will, in the end, turn out to have far outweighed the loss, even to the extent of making the ban itself worthwhile. What the bells of England really mean to the people of England, we should never have known without these three years of silence. The victory ringing of last November was a most surprising revelation, even to those of us who knew something of the part church bells have played in the past in the life of ordinary men. But that event by itself might have deceived us. There were then special reasons why people should have been attracted to the sound of bells.

Jonathan Stuart: [00:49:33] The feeling of joy and relief that a victory had been won, which gave real hopes that the tide of war had turned at last. The dramatic announcement of the ringing by the Prime Minister at the climax of his great speech. These were almost enough in themselves to focus attention on the bells. But that event did not stand alone. We have had continued and abundant evidence, and not least in these last few weeks, that church bells mean much in the life of this country. Not so long ago, there was a general impression that the public cared nothing for bells and would have welcomed any official action to suppress or curtail their use. We know better now. We have the general public with us and we have the press with us. When great journals like The Times, The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Mail and the Sunday Times publish leaders such as they have done during these last few weeks, we can look in the face with confidence any enemies we may have. Let us not forget too, that altogether, apart from us Ringers and our particular interests, the Church of England values her bells and will use her vast influence in their defence. These broadly are our loss and our gain. It is our part now to do our best to replace the loss and to see to it that we do not by foolish and shortsighted action, throw away our gain.

Cathy Booth: [00:51:12] To put this story together, I received relevant sections of the Ringing World from Alan Regin. One small article from the 11th of December 1942 reads as follows:

Andrew Booth: [00:51:23] We are glad to hear that official information is being received that Mr. Dennis Brock, Mr. Kenneth Spackman, previously reported missing, are now prisoners of war in Italian hands. Mr. Dennis Brock is a member of the band at Sunbury on Thames.

Cathy Booth: [00:51:37] We're very lucky to hear Alan interviewing Dennis on the telephone about his struggle to get home at the end of the war.

Alan Regin: [00:51:45] Dennis, as the war came to a close, I believe that you were in or close to Dresden. Can you explain a little about where you were and what happened at the time?

Dennis Brock: [00:51:58] As the war came to a close, I was working under the German army in Dresden. We had been working on the railway at night on the postal system, unloading passenger trains which were packed to the roof with mail and sorting it out so that it went to the different branches of the Post Office in Dresden. They had postcodes in those days, similar to ours today. Dresden was 008 and we had to sort all that out so it could be taken away by road transport. The German guards had begun to be lax in discipline and disobey orders. It was highly unusual for them to do that. I think they were frightened of the very severe air raids that they were having at that time. They'd had the worst air raids on the war, I think, apart from the Tokyo one on the 13th of February 1945.

Alan Regin: [00:53:07] I seem to recall you telling me that the guards kind of disappeared?

Dennis Brock: [00:53:12] Well, they did. On one night, virtually the war was over. But the guards, they took off their uniform and flung them aside and went home. We were left without guards. It was very unsettling. We weren't sure what we should do. We decided the best thing to do was to group up and put some NCOs in charge and walk out. Well we walked out one morning, we opened the gate ourselves and walked out and walked down the road towards the city of Dresden. But when we got down to the city, we found that other camps were doing the same. So we marched off just like a British brigade into the countryside. We were quite surprised that we were receiving help from farmers. It was lovely weather.

Alan Regin: [00:54:13] So you got help from the locals as you made your way towards the allied line?

Dennis Brock: [00:54:20] We were making our way, at that time hopeful of meeting with the Americans, which we did eventually. We lived off the countryside and slept on the roadside at night and every village we went to we were welcomed. We got some food, some form of snack, drink, a bit weak. It was enough to help. Gradually, we came nearer and nearer to the American army, and the first American I saw was in a Jeep as an officer. He told me the American army was about five kilometers away to the west of us. If we kept walking through the villages. We went into one or two houses and we were given pretty rough sandwiches as the day when we walked and walked, and we got nearer the heart of the American army and they took us in. We spent the night round a huge bonfire. We had been washing our clothes, our clothes were filthy. So we decided to have an open air bath. But by daylight, we were clean and dry. We went to Cologne. We spent the night in Brussels, in a school and they fed us, gave us the opportunity to have a bath, which we did. And the next morning, we were taken by lorry by British Air Force over to the other side of Brussels.

Dennis Brock: [00:56:04] Well, we were flown home to just outside of... When we touched down, it was pouring with raining, we were back to normal,

Alan Regin: [00:56:15] -good old English, weather-.

Dennis Brock: [00:56:18] Yes, that was it. We landed just outside of ... We were taken straight away in a land rover, I think, over to a hangar. Well, huge bread and cheese sandwiches and half a pint of beer. After that, we were taken to a little place near Chalfont St Giles for a bath, to clean up and new clothes. We didn't go home for three days. A lot of medical attention, we got that, money, ration cards. All we would need as civilians, it was all terribly perfect run. The best organization you could ever expect.

Alan Regin: [00:57:06] Oh, that's fantastic, Dennis. So Dennis, can you remember where you were on VE Day and perhaps talk about what you did that day?

Dennis Brock: [00:57:18] VE Day was on a Wednesday. Well, I was travelling across Saxony, around Dresden, trying to link up with the British Army, and I made it with some of my pals. I offered about 20 of them to come with me. They, some of them thought that would be better off going with the Russians. And they went with the Russians, to Odessa on the Black Sea. I'd had enough of this place. So I went my way to the West and I said to the boys, "If anyone wants to come with me, do so. You won't get into trouble from the British Army. So I'll see to that." And about eight of them came in and we got home. The others, this was in May we got home, but the others didn't get home from Russia until September. They didn't suffer terrible hardship. They had a very, very good time there.

Alan Regin: [00:58:37] So how quickly after the war did you manage to get back to ringing?

Dennis Brock: [00:58:42] Very quickly, I got home on the Wednesday. Early in May. When I got home, naturally I went to my girlfriend. In the evening as we walked out of the village, the bells started ringing and I found out the vicar and the Hersham ringers had got together with some of the Walton ringers and what was left of ours. Most of the men had gone to the war. And so Hersham and Walton, they joined together and they rang our bells with one or two of our old boys. But on the following Sunday, I rang in the morning at Sunbury.

Alan Regin: [00:59:31] So the Sunday after you arrived back that was your first ring, but you heard the bells on the Wednesday before that.

Dennis Brock: [00:59:39] Yes, I rang, I heard the bells on the Wednesday. I was there with my girlfriend. A couple of days later, on the weekend, I was able to walk properly. And I went down to church, about a half past nine and we pulled the bells up. We rang. We rang Grandsire triples. It was wonderful. Various people in the village said, "Oh, there's the bells, Dennis must be back".

Alan Regin: [01:00:17] That's absolutely wonderful. And I think we should remind listeners that on your one hundredth birthday, you also rang Grandsire triples at Sunbury.

Cathy Booth: [01:00:30] The peals and quarter peals that Dennis has rung, have been reported in the Ringing World as all such ringing is.

Les Boyce: [01:00:40] Peals and quarter peals rung to celebrate the victory were published in the Ringing World magazine on the 18th and 25th of May 1945. It is interesting that in the days before the internet, peals appeared in print within 10 days. Although the Postal Service was different then. Many of the peals were of simpler methods such as Plain Bob major with occasional more complex peals. The only 12 bell peal was at Leicester Cathedral, conducted by Harold J. Paul. This caught our eye as his wife, who rang alongside him, was listed as Mrs H.J. Paul. The vast majority of Ringers in the other peals were also male. Another sign of those different times. The footnotes were short, so it is difficult to know more about the story behind many of the peals. Today, we are used to seeing notes explaining the reasons for ringing, such as a birthday or wedding anniversary celebration, personal milestones in a ringing career, or to mark a special occasion in church life. Footnotes in the victory peals were deliberately restricted to simply recording those who rang their first peal. The editor of the Ringing World commented "There can be no doubt that for the people of England, the sound of bells, except when it is to call people to prayer can mean one thing and one thing only. Everything else must give place to that".

Les Boyce: [01:02:21] The editor was only prepared to make an exception for muffled peals in memory of the deceased. Nevertheless, it is still interesting to see that, three people rang their first peal at Cawthorne in Yorkshire, at Prittlewell near Southend in Essex and at Wool in Dorset. Four people rang their first peal at Rodbourne Cheney near Swindon, in Wiltshire and at Haresfield in Gloucestershire. Even more extraordinary is that five people rang their first peal at Dinda in Somerset at Bury St Edmunds Cathedral and at Bray in Berkshire. Not only is five people ringing their first peal together quite an achievement and hardly ever achieved nowadays. But the tenor bells at Bray and Bury St Edmunds are around one and a half tonnes, which is heavy. Well over three hours ringing would have been thirsty work in May. The editorial on the 18th of May also commented that "since the outbreak of war, the attitude of the people towards bells has been different to what it had been for many years before", and encouraged ringers to retain that respect and support by remembering that the bells should be rung so that they give pleasure to those who hear them outside.

Cathy Booth: [01:03:47] And now we are going to listen to Alan, talk to Eric Hitchens, who was one of those who rang their first peal on VE Day.

Alan Regin: [01:03:55] Eric, I understand that you learnt to ring before the end of World War Two. Could you explain to listeners how that came about, where you were, and what happened? Perhaps who taught you and who else was involved?

Eric Hitchens: [01:04:10] Okay. It really evolved around the situation of when the ringing was being possibly becoming available again following El Alamein. Percy Harding, who was a tower captain at North Bradley in Wiltshire and which is the parish in which we lived as a family. He had the foresight to think that in order to get the bells moving again, more ringers would be needed, and he chose to look at the choir as being a possible source. And indeed, that's certainly what happened. He invited us to come up to the tower. He must have been quite persuasive because all of us decided that that's what we would like to do. And so that's where it started. Of course, at this time, the ban was still fully on, and therefore the whole issue began with us being taught to handle our bells with the bells silent. And we progressed accordingly in that way. And subsequently, when the ban was lifted or when ringing was allowed again, we were obviously able to take part. I was only 11 at that time. I was the youngest of three of us. And in 1942, I guess I stood up with the bullying from my brother and others. So we progressed. And obviously by this time, no doubt, the fact of V-J Day or any day such as that, was coming to light and therefore we were well in advance. And by the time that VE Day was likely to take place, we were all capable ringers.

Alan Regin: [01:05:54] Now, Eric, I understand that VE Day was actually a very special day in your personal ringing journey. Can you tell us about the day and what you and the band at North Bradley achieved?

Eric Hitchens: [01:06:09] Well, what we achieved. We met, first of all, because of the morning's service actually on that day and we rang for the service, for a service of dedication, really. And after the service came some lunchtime and then we were then scheduled to be on parade at three o'clock in the afternoon. I was ringing my first peal. I was stood in the tower thinking, what on the Earth is this going to be all about. Needless to say, the two others in the band were actual first timers as well. So we were quite happy to go ahead and there was myself, my brother, Ron Harding, who was at the previous ringing, [inaudible] who was a new ringer like myself, Percy Harding, who called the peal, A.R Harding. And so there were three new ones and three old ones, if you like in the band as it stood that day. And we rang the peal of Grandsire doubles and I rang the treble, so I was first home. And so that was it. So we were then effectively I suppose accomplished 2 hours and 51 minutes. I'm sure at the time I wondered how on earth I could stand still in one place for all that time. But it passed eventually, and therefore we came to be in the record books.

Alan Regin: [01:07:32] Well, that's absolutely fantastic Eric. So and also because that was on VE Day. Can you tell us what else went on in the village and what things happened after you left?

Dennis Brock: [01:07:45] On VE Day, which I had previously mentioned, that was very much the Sunday service and so on. But VE Day was actually a two day holiday or two day parade. And of course, the school children were delighted over that because they didn't have to go to school. But needless to say, the local people in the village had decorated the village hall and made arrangements for the meal and a celebrations of all sorts. So yes, it was celebrated as Children's day.

Eric Hitchens: [01:08:19] And I quote now from what said that to Miss Coalhurst, who lives next door to us, actually organised a party in the progressive hall. The hall was decorated and food was provided by people from North Hadley and beyond. There must have been 150 children there. We had a wonderful feast and a great singsong.

Alan Regin: [01:08:42] Was it the case, Eric, that food was reasonably difficult to come by?

Eric Hitchens: [01:08:47] Well, I suppose so. I said all these ingenious ladies and cooks and people, managed to find the necessary resources.

Alan Regin: [01:08:56] Well, that's fantastic, thank you Eric, for sharing your story with us. That's wonderful.

Eric Hitchens: [01:09:02] Just as a closure if I may. Of the three of us who rang their first peal that day and another one who joined us afterwards. Unfortunately, though, they've all passed by the wayside. I'm the last one holding the flag.

Alan Regin: [01:09:14] Absolutely. And how old are you now, Eric?

Eric Hitchens: [01:09:17] I should be 90 in November. Of course, the youngest. All the others, I sadly lost my brother, Lawrence, who was in it. He passed away last year, so I'm hanging on, hanging on.

Alan Regin: [01:09:31] Well, very glad to hear that you're still going strong Eric.

Eric Hitchens: [01:09:34] And thank you for this. It's brought back some delightful memories.

Steve Johnson: [01:09:38] And so to sum up, in World War Two, the bells were initially assigned what might have sounded like an important role in the defense of the country, but was in effect, a ban on ringing. It took over two years, but this ban was lifted by an order at the highest level in the land and before the end of the war. Having initially supported the government line, the Ringing World afterwards called it little more than rather stupid bureaucratic interference. After the ban, we can see with the benefit of hindsight, that ringing did recover and with renewed confidence and the affection of the British people for their bells was fully revealed. Bell Ringers rang in force on VE Day so that many people only remember the ban and the bells ringing again on that day. Leading historians often get this story wrong. We can learn many lessons from what the bell ringers did when confronted with the ban in World War Two. Their inventiveness and their optimism and their determination to practice their ringing throughout. And what of today's ban? Bell ringers are increasingly using technology to sustain their absorbing fascination with the art. More of that in a later episode of Fun with Bells. For now, we should follow the advice stay home, protect the NHS and save lives. But look forward, as our ringing forebears did to the day when bell ringing resumes and the sound of bells will once more be a part of the soundscape.

Steve Johnson: [01:11:14] The readers in this episode were in order of appearance. Steve Johnson of St Mary at Bow London, Simon Davies of Kensington, Jill Belcher of Earl Shilton, Bob Christopher of Maids Morton, Graham Nabb Of Kineton, Nick Brett of Rugby, Phil Tremain of St Columb Major, Natalie Brett of Rugby. Jenny Lawrence of Maven. Simon Linford of St. Martin's Birmingham. President of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Andrew Wilby of Towcester and the Taylors Bell Foundry. Stephen Hoare of Thame. Chris Wright of Kildwick. Andrew Johnson of Twyford. Judith Frye of Dunblane. Simon Head of Woughton on the Green. Chris Bullied of Pattishall. Stuart Newton of St Annes on the Sea. Alison Davies of Whipsnade and Marsworth, Richard Booth of Marsworth, Oliver Bouckley of Wolverhampton, Matthew Turner of Rumney, Cardiff. Helen MacGregor of Alderney in the Channel Islands, Jonathan Stuart of Pattishall. Andrew Booth of New Alresford and Les Boyce of Tiverton. We also heard the voices of Alan Regin, steward of the Rolls of Honour, who curated the articles from the Ringing World and interviewees Dennis Brock and Eric Hitchens. The recorded bells of Great St Mary's Cambridge, were rung by the Society of Cambridge youths. Our thanks also go to Lesley Belcher, Chair of the Association of Ringing Teachers, who support this podcast series. Sue Hall for the podcast artwork, Anne Tansley-Thomas, who wrote the show notes. Rose Nightingale, who coordinated the readers and their contributions. Beth Johnson and David Smith for their article in the Ringing World. Vicki Chapman of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, Roger Booth for script assistance and editorial consultant John Gwynne. Technical support was provided by Steve Johnson. Fun with Bells is devised, produced and presented by Cathy Booth.

[01:13:20] [Bells ringing]